Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is a sudden, unexpected death caused by loss of heart function (sudden cardiac arrest). Sudden cardiac death is responsible for half of all heart disease deaths.

Sudden cardiac death occurs most frequently in adults in their mid-30s to mid-40s, and affects men twice as often as it does women. This condition is rare in children, affecting only 1 to 2 per 100,000 children each year.

Sudden cardiac arrest is not a heart attack (myocardial infarction). Heart attacks occur when there is a blockage in one or more of the coronary arteries, preventing the heart from receiving enough oxygen-rich blood. If the oxygen in the blood cannot reach the heart muscle, the heart becomes damaged.

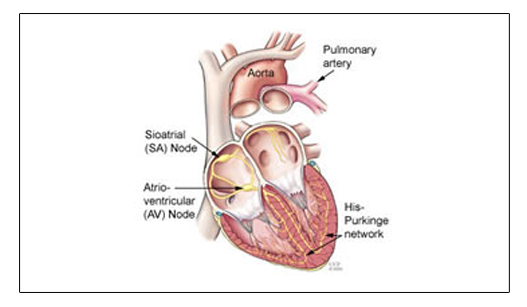

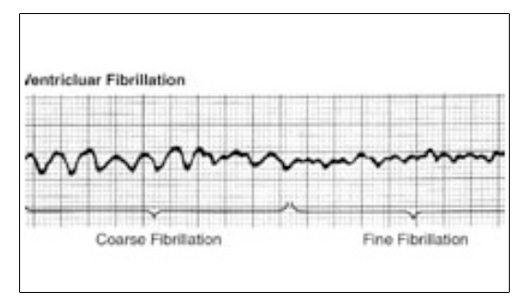

In contrast, sudden cardiac arrest occurs when the electrical system to the heart malfunctions and suddenly becomes very irregular. The heart beats dangerously fast. The ventricles may flutter or quiver (ventricular fibrillation), and blood is not delivered to the body. In the first few minutes, the greatest concern is that blood flow to the brain will be reduced so drastically that a person will lose consciousness. Death follows unless emergency treatment is begun immediately.

Emergency treatment includes cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and defibrillation. CPR keeps enough oxygen in the lungs and gets it to the brain until the normal heart rhythm is restored with an electric shock to the chest (defibrillation). Portable defibrillators used by emergency personnel, or public access defibrillators (AEDs) may help save the person’s life.

Some people may experience a racing heartbeat or they may feel dizzy, alerting them that a potentially dangerous heart rhythm problem has started. In over half of the cases, however, sudden cardiac arrest occurs without prior symptoms.

Most sudden cardiac deaths are caused by abnormal heart rhythms called arrhythmias. The most common life-threatening arrhythmia is ventricular fibrillation, which is an erratic, disorganized firing of impulses from the ventricles (the heart’s lower chambers). When this occurs, the heart is unable to pump blood and death will occur within minutes, if left untreated.

There are many factors that can increase a person’s risk of sudden cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death. The two leading risk factors include :

Previous heart attack (75 percent of SCD cases are linked to a previous heart attack) - A person’s risk of SCD is higher during the first six months after a heart attack.

Coronary artery disease (80 percent of SCD cases are linked with this disease) -Risk factors for coronary artery disease include smoking, family history of cardiovascular disease, high cholesterol or an enlarged heart.

Other risk factors include:

Ejection fraction of less than 40 percent, combined with ventricular tachycardia (see information below about EF)

Prior episode of sudden cardiac arrest

Family history of sudden cardiac arrest or SCD

Personal or family history of certain abnormal heart rhythms, including long QT syndrome, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, extremely low heart rates or heart block

Ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation after a heart attack

History of congenital heart defects or blood vessel abnormalities

History of syncope (fainting episodes of unknown cause)

Heart failure: a condition in which the heart’s pumping power is weaker than normal. Patients with heart failure are 6 to 9 times more likely than the general population to experience ventricular arrhythmias that can lead to sudden cardiac arrest.

Dilated cardiomyopathy (cause of SCD in about 10 percent of the cases): a decrease in the heart’s ability to pump blood due to an enlarged (dilated) and weakened left ventricle

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy : a thickened heart muscle that especially affects the ventricles

Significant changes in blood levels of potassium and magnesium (from using diuretics, for example), even if there is not organic heart disease

Obesity

Diabetes

Recreational drug abuse

Taking drugs that are “pro-arrhythmic” may increase the risk for life-threatening arrhythmias

Sudden cardiac arrest can be treated and reversed, but emergency action must take place immediately. Survival can be as high as 90 percent if treatment is initiated within the first minutes after sudden cardiac arrest. The rate decreases by about 10 percent each minute longer. Those who survive have a good long-term outlook.

If you witness someone experiencing sudden cardiac arrest, immediately call your local medical emergency personnel and initiate CPR. If done properly, CPR can save a person’s life, as the procedure keeps blood and oxygen circulating through the body until help arrives.

If an AED (Ambulatory External Defibrillator) is available, the best chance of rescuing the patient includes defibrillation with that device. The shorter the time until defibrillation, the greater the chance the patient will survive. It is CPR plus defibrillation that rescues the patient.

Once emergency personnel arrive, defibrillation can be used to restart the heart. This is done through an electric shock delivered to the heart through paddles placed on the chest.

After successful defibrillation, most patients require hospital care to treat and prevent future cardiac problems.

If you have any of the risk factors listed above, it is important to speak with your doctor about how to reduce your risk.

Keeping regular follow-up appointments with your doctor, making certain lifestyle changes, taking medications as prescribed and having interventional procedures or surgery (as recommended) are ways you can reduce your risk.

Follow - up care with your doctor :

Your doctor will tell you how often you need to have follow-up visits. To prevent future episodes of sudden cardiac arrest, your doctor will want to perform diagnostic tests to determine what caused the cardiac event. Tests may include electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG), ejection fraction, ambulatory monitoring, echo-cardiogram, cardiac catheterization and electrophysiology study.

Ejection fraction (EF):

Ejection fraction is a measurement of the percentage of blood pumped out of the heart with each beat. Ejection fraction can be measured in your doctor’s office during an echocardiogram (echo) or during other tests such as a multiple gated acquisition (MUGA) scan, cardiac catheterization, nuclear stress test or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the heart.

The Ejection fraction of a healthy heart ranges from 55 to 65 percent. Your Ejection fraction can go up and down, based on your heart condition and the effectiveness of the therapies that have been prescribed.

If you have heart disease, it is important to have your Ejection fraction measured initially, and then as needed, based on changes in your condition. Ask your doctor how often you should have your Ejection fraction checked.

Reducing your risk factors :

If you have coronary artery disease (and even if you do not) there are certain lifestyle changes you can make to reduce high blood pressure and cholesterol levels and manage your diabetes and weight, thereby reducing your risk of sudden cardiac arrest.

These lifestyle changes include :

Quitting smoking

Losing weight if overweight

Exercising regularly

Following a low-fat diet

Managing diabetes

Managing other health conditions

If you have questions or are unsure how to make these changes, talk to your doctor.

Patients and families should know the signs and symptoms of coronary artery disease and the steps to take if symptoms occur.

Medications :

To help reduce the risk of sudden cardiac arrest, doctors may prescribe medications to patients who have had heart attacks, or who have heart failure or arrhythmias. These medications may include angiotensin- converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers and other antiarrhythmics. For patients with high cholesterol and coronary artery disease, statin medications may be prescribed.

If medication is prescribed, your doctor will give you more specific instructions.

Sudden cardiac death and athletes

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) occurs rarely in athletes, but when it does happen, it often affects us with shock and disbelief.

Cause

Most cases of SCD are related to undetected cardiovascular disease. In the younger population, SCD is often due to congenital heart defects, while in older athletes (35 years and older), the cause is more often related to coronary artery disease.

Prevalence

Although SCD in athletes is rare, media coverage often makes it seem like it is more prevalent. In the younger population, most SCD occurs while playing team sports; in about one in 100,000 to one in 300,000 athletes, and more often in males. In older athletes (35 years and older), SCD occurs more often while running or jogging – in about one in 15,000 joggers and one in 50,000 marathon runners.

Screening

The American Heart Association recommends cardiovascular screening for high school and collegiate athletes, which should include a complete and careful evaluation of the athlete’s personal and family history and a physical exam. Screening should be repeated every two years, and a history should be obtained every year.

Men aged 40 and older and women aged 50 and older should also have an exercise stress test and receive education about cardiac risk factors and symptoms.

If heart problems are identified or suspected, the athlete should be referred to a cardiologist for further evaluation and treatment guidelines before

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) :

For patients who have a great risk for SCD, an ICD may be inserted as a preventive treatment. An ICD is a small machine similar to a pacemaker that is designed to correct arrhythmias. It detects and then corrects a fast heart rate.

The ICD constantly monitors the heart rhythm. When it detects a very fast, abnormal heart rhythm, it delivers energy (a small, but powerful shock) to the heart muscle to cause the heart to beat in a normal rhythm again. The ICD also records the data of each episode, which can be viewed by the doctor through a third part of the system that is kept at the hospital.

The ICD may be used in patients who have survived sudden cardiac arrest and need their heart rhythms constantly monitored. It may also be combined with a pacemaker to treat other underlying irregular heart rhythms.

Interventional procedures or surgery :

For patients with coronary artery disease, an interventional procedure such as angioplasty (blood vessel repair) or bypass surgery may be needed to improve blood flow to the heart muscle and reduce the risk of SCD. For patients with other conditions, such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or congenital heart defects, an interventional procedure or surgery may be needed to correct the problem. Other procedures may be used to treat abnormal heart rhythms, including electrical cardioversion and catheter ablation.

When a heart attack occurs in the left ventricle (left lower pumping chamber of the heart), a scar forms. The scarred tissue may increase the risk of ventricular tachycardia. The electro physiologist (doctor specializing in electrical disorders of the heart) can determine the exact area causing the arrhythmia. The electro physiologist, working with your surgeon, may combine ablation (the use of high-energy electrical energy to “disconnect” abnormal electrical pathways within the heart) with left ventricular reconstruction surgery (surgical removal of the infarcted or dead area of heart tissue).

Educate your family members :

If you are at risk for SCD, talk to your family members so they understand your condition and the importance of seeking immediate care in the event of an emergency. Family members and friends of those at risk for SCD should know how to perform CPR.